This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

About Lime

Building limes have been used as binders in mortars and plasters for thousands of years; the earliest surviving example dates from around 8000 BC in a floor in Turkey. Limes were the principal binders for the major building and civil engineering projects of the Roman Empire over 2,000 years ago.

Limes continued in use as one of the principal binders for all forms of construction, including castles, cathedrals, bridges, harbours and canals until the last century, not only in Europe, but worldwide.

It was only the introduction of cement in the middle of the 19th century which led to the decline in the use of lime, culminating in its virtual disappearance by the mid 20th century.

Emerging evidence in the 1970s of the damage caused to historic buildings by the use of cement mortars and modern plasters has led to a revival in the use of lime over the past 40 years, not only for conservation but also for new build, see Why Use Lime.

There are two principal types of lime

1. Pure Lime which is also known as:

- air lime, because it hardens on exposure to air

- fat lime, from its consistency in putty form

- high calcium lime

- non-hydraulic lime

2. Hydraulic Lime, also known as water lime, as it sets under water

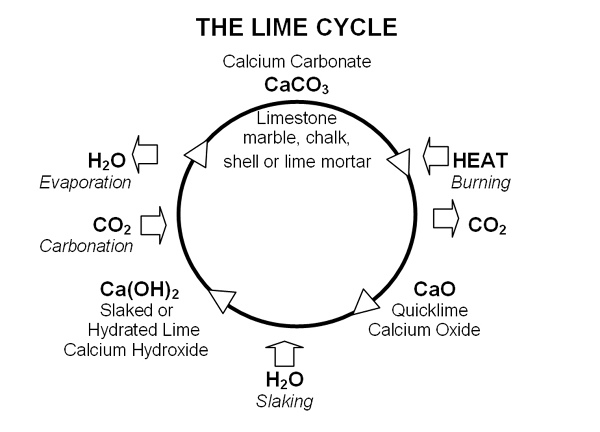

The production process is interesting. First, quicklime is created by burning limestone, marble, chalk or shell at above 900ºC to drive off carbon dioxide. If the material being burnt is pure calcium carbonate, then pure quicklime is produced. If the material being burnt contains impurities, typically aluminium and magnesium silicates, then hydraulic quickime is produced.

Lime is created by adding quicklime to water, referred to as ‘slaking’. With hydraulic quicklime sufficient water is used to produce a dry powder. Pure lime is produced either as putty or a powder. The powder is also known as:

- Builders’ lime, because it is generally available from builders merchants and is used by builders to gauge cement mortars,

- Hydrated lime or dry hydrate, which is confusing because all lime is hydrated by virtue of having had water added.

Lime is the basic ingredient in mortars, plaster and limewashes. Lime mortar is lime is mixed with an aggregate. Lime plasters have a finer aggregate and normally also have animal hair added. Lime mixed with water forms limewash which can also have pigment added.

When exposed to air, both pure lime and hydraulic lime mortars and plasters harden by reabsorbing carbon dioxide to become calcium carbonate again. This is called carbonation. In addition, in hydraulic lime mortars, the silicates produce a chemical set.

The following diagram illustrates the processes:

Pure lime mortars and plasters made from putty or powder can be used for many building purposes other than externally in exposed positions.

Putty is generally considered to be more reliable but provided mortars and plasters made from powder are allowed to mature for a few days prior to use, satisfactory results may be achieved.

An accelerated chemical set can be induced in pure lime mortars and plasters by the addition of pozzolans, such as clays, brick dust or volcanic ash which provide the necessary silicates.

Hydraulic lime mortars and plasters set faster and harder than pure limes and are more often used for exterior coatings and masonry, especially in exposed or damp situations. The strength of the chemical set increases with the proportion of silicates.

At high strength, these become as strong as cement, though never as hard, brittle or impermeable. Pure limes, hydraulic limes and cements form a broad spectrum of materials, click here for an article on the lime spectrum, reproduced by permission of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

Limewash, which is used for coating both external and internal masonry and plaster, is, in its simplest form, produced by mixing either pure or hydraulic lime with water to a thin cream consistency.

For further reading, see the BLF Bookstall.

In this section

Become a member

Members of the Building Limes Forum form a community of lime enthusiasts and practitioners, most of whom are producers, suppliers, specifiers or users of lime.

Useful documents

Contact Building Limes Forum

Building Limes Forum

Riddle’s Court

322 Lawnmarket

Edinburgh, EH1 2PG, UK